History Repeats With the Personal Robot

History Repeats With the Personal Robot

For those old enough to remember the early days of personal computers, it's hard not to notice how closely the development of personal robots mirrors that of their less ambulatory computer relatives. In fact, the parallels are uncanny.

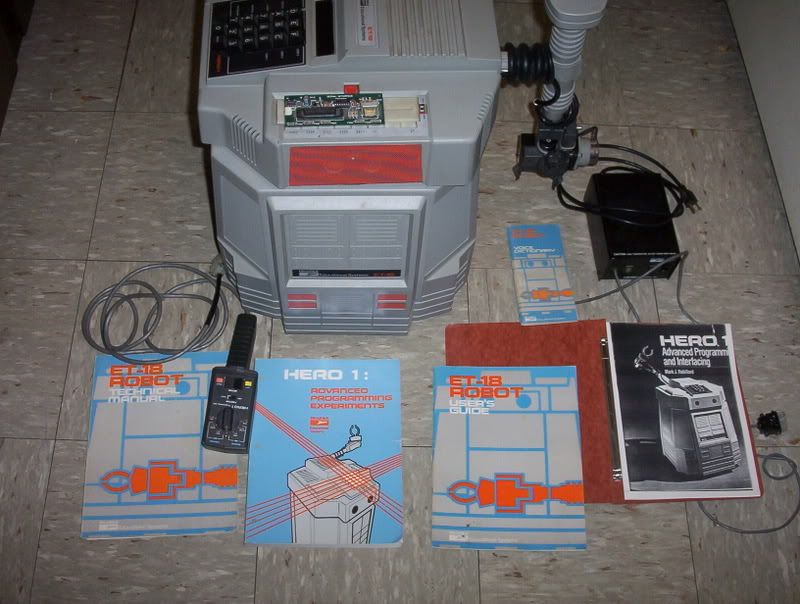

Back in 1975 or so, personal computers were the exclusive domain of hobbyists, chiefly ham radio and model railroad enthusiasts. Companies like MITS, Cromemco, Ohio Scientific, IMSAI, and a number of others offered computer kits, and a number of other companies sprang up to provide peripherals and add-ons for them. Although I was hardly more than a tyke at the time, I helped assemble an IMSAI 8080, which had to be programmed by means of toggle switches on the front panel. Assembling a computer from a kit provided a great deal of satisfaction and sense of accomplishment.

Robots are now at an similar rudimentary stage of development. Currently, hobbyists are the primary buyers of robot kits, and the assembled robots are relatively crude, as were the first personal computers. But one needs only to look at the evolution of computers to realize that robots will almost certainly follow the same developmental cycle, only much more rapidly. After all, robots have already benefitted tremendously from advances in computer design. We'll soon see the next evolutionary stage in robots. The coming robot designs will be more sophisticated and capable than their predecessors. An analogy with computers would be the Apple II, which hit the market in 1977, upping the ante considerably; the S-100 bus computers were quickly eclipsed by the Apple II's polish and sophistication. For the first time, non-hobbyists began to get interested. The robot counterpart to the Apple II is just around the corner. Somewhere out there, right this minute, is a Woz. Maybe it's Takahashi-san, or perhaps it's someone we haven't heard about yet.

Robots, like any product, are market-driven. Companies are catching on that a profitable market exists. The challenge will be to broaden this market so that robots will appeal to buyers other than hard-core solder-jockeys. To accomplish that, the designs will necessarily become more polished than current models. Exposed servos and wiring will be a thing of the past, covered by bodywork designed by stylists. Hand-held remote control will no doubt also fade into history; buyers will insist on voice control and some degree of autonomy in their robots. Object avoidance, effectors to manipulate objects, some awareness of environment -- all are necessary if the fledgling robot industry is to progress beyond its current stage.

Initially, personal robots need not be capable of performing useful, utilitarian tasks in order to be as successful as computers at the same stage of development. Eventually, they'll do all kinds of useful work, but in the short-run it will be enough that robots provide entertainment and a measure of companionship for their owners, most of whom will not be programmers, and wouldn't know what a servo was if they found one in their mashed potatoes. In fact, the first company to design a robot that can mimic a toddler will likely find a significant market among folks who are childless or who feel their children have grown too quickly.

One thing's certain -- the personal robot industry is poised to take off. And we've got front-row seats. Future robot owners will no doubt hear a few old timers say, "I remember when these robots were only a fifth the size they are now, and you had to put 'em together yourself, and all their innards were exposed, and you used a hand-held remote or connected 'em to a computer to make 'em do anything." The listeners will probably roll their eyes. They won't have a clue how exciting these "primitive" times were.

I guess you had to be there.

Back in 1975 or so, personal computers were the exclusive domain of hobbyists, chiefly ham radio and model railroad enthusiasts. Companies like MITS, Cromemco, Ohio Scientific, IMSAI, and a number of others offered computer kits, and a number of other companies sprang up to provide peripherals and add-ons for them. Although I was hardly more than a tyke at the time, I helped assemble an IMSAI 8080, which had to be programmed by means of toggle switches on the front panel. Assembling a computer from a kit provided a great deal of satisfaction and sense of accomplishment.

Robots are now at an similar rudimentary stage of development. Currently, hobbyists are the primary buyers of robot kits, and the assembled robots are relatively crude, as were the first personal computers. But one needs only to look at the evolution of computers to realize that robots will almost certainly follow the same developmental cycle, only much more rapidly. After all, robots have already benefitted tremendously from advances in computer design. We'll soon see the next evolutionary stage in robots. The coming robot designs will be more sophisticated and capable than their predecessors. An analogy with computers would be the Apple II, which hit the market in 1977, upping the ante considerably; the S-100 bus computers were quickly eclipsed by the Apple II's polish and sophistication. For the first time, non-hobbyists began to get interested. The robot counterpart to the Apple II is just around the corner. Somewhere out there, right this minute, is a Woz. Maybe it's Takahashi-san, or perhaps it's someone we haven't heard about yet.

Robots, like any product, are market-driven. Companies are catching on that a profitable market exists. The challenge will be to broaden this market so that robots will appeal to buyers other than hard-core solder-jockeys. To accomplish that, the designs will necessarily become more polished than current models. Exposed servos and wiring will be a thing of the past, covered by bodywork designed by stylists. Hand-held remote control will no doubt also fade into history; buyers will insist on voice control and some degree of autonomy in their robots. Object avoidance, effectors to manipulate objects, some awareness of environment -- all are necessary if the fledgling robot industry is to progress beyond its current stage.

Initially, personal robots need not be capable of performing useful, utilitarian tasks in order to be as successful as computers at the same stage of development. Eventually, they'll do all kinds of useful work, but in the short-run it will be enough that robots provide entertainment and a measure of companionship for their owners, most of whom will not be programmers, and wouldn't know what a servo was if they found one in their mashed potatoes. In fact, the first company to design a robot that can mimic a toddler will likely find a significant market among folks who are childless or who feel their children have grown too quickly.

One thing's certain -- the personal robot industry is poised to take off. And we've got front-row seats. Future robot owners will no doubt hear a few old timers say, "I remember when these robots were only a fifth the size they are now, and you had to put 'em together yourself, and all their innards were exposed, and you used a hand-held remote or connected 'em to a computer to make 'em do anything." The listeners will probably roll their eyes. They won't have a clue how exciting these "primitive" times were.

I guess you had to be there.

I was there, and I agree with you. Actually, I missed the early part - the first computer I used was a Commodore PET, and my first computer I owned was an Apple //c.

It will be interesting to see how the internet, with all the sharing and collaboration, will shape the robotics revolution in a way that wasn't available back in the Apple ][ days...

- Jon

It will be interesting to see how the internet, with all the sharing and collaboration, will shape the robotics revolution in a way that wasn't available back in the Apple ][ days...

- Jon

You both have two great points but all you have to do is to go over to Iraq and Afghanistan. The robotic revolution is going full stream there. There is thousands upon thousands of robots of all different types being used by American and British troops. There are some many different types of robots that I could not list them all here.

I think what we're talking about is the autonomous robot revolution, which very clearly hasn't started. The military robots, while showcasing some interesting and impressive technology, are pretty much all remote control.

One thing they help with in respect to the real robot revolution is to get people used to the idea of these little robots trundling around, accomplishing things. Eventually they will be autonomous, and the people "using" them will give the robots orders directly instead of telling the operator what to do.

- Jon

One thing they help with in respect to the real robot revolution is to get people used to the idea of these little robots trundling around, accomplishing things. Eventually they will be autonomous, and the people "using" them will give the robots orders directly instead of telling the operator what to do.

- Jon

While I agree that the robots in iraq and afghanistan are useful and are saving lives, the robotic revolution being discussed here is that of the personal robot. The robots used in these hot spots don't really fall into this category.

I think that the first group of truly helpful personal robots will be info servers. At this time it is hard to design a robot capable of doing any complex task, but this does not mean that robots can't be useful. Computers are already used to organize our lives. For instance, we keep our schedules on computers, pay our bills online, and use the Internet to communicate. Devices to do all of these things have been getting smaller and smaller. The next step is to turn this technology into a robot. PDA's take on a whole new meaning. The key to making this type of personal robot effective is development of the robot to human interface. The more that the robot can be communicated and directed through speech the more natural of a companion it becomes.

The next group of personal robots are capable of doing complex chores, and some where around this time the first truly useful humanoids are introduces. (yes i am implying that asimo isn't really useful. impressive, but not useful). Does anyone want to venture to guess when the market really starts to take off, and things get really big?

I think that the first group of truly helpful personal robots will be info servers. At this time it is hard to design a robot capable of doing any complex task, but this does not mean that robots can't be useful. Computers are already used to organize our lives. For instance, we keep our schedules on computers, pay our bills online, and use the Internet to communicate. Devices to do all of these things have been getting smaller and smaller. The next step is to turn this technology into a robot. PDA's take on a whole new meaning. The key to making this type of personal robot effective is development of the robot to human interface. The more that the robot can be communicated and directed through speech the more natural of a companion it becomes.

The next group of personal robots are capable of doing complex chores, and some where around this time the first truly useful humanoids are introduces. (yes i am implying that asimo isn't really useful. impressive, but not useful). Does anyone want to venture to guess when the market really starts to take off, and things get really big?

sthmck wrote:The next group of personal robots are capable of doing complex chores, and some where around this time the first truly useful humanoids are introduces. (yes i am implying that asimo isn't really useful. impressive, but not useful). Does anyone want to venture to guess when the market really starts to take off, and things get really big?

That's a good question, and one I've been thinking about. If the analogy with personal computers holds up, critical mass will be reached when a big player enters the market with a next-gen robot at a reasonable price-point. The game changed when Apple entered the market, as mentioned previously, but it really ramped up when IBM introduced its PC in 1981. So it took six years for personal computers to achieve critical mass. Given the existence of the Internet and the information sharing it makes possible, and the fact that technology is significantly more advanced than it was in 1975, I predict that critical mass for personal robots will be reached in less time, perhaps two to three years.

And yes, autonomy will be crucial to this revolution's success. Without autonomy, it's not much different than driving an RC car that has legs, despite some canned movement sequences. Most people would get tired of that in a hurry. The technology exists for at least semi-autonomous robots. It remains for some forward-thinking company to put it all together in a package at a reasonable price. The "reasonable price" part is the stumbling block at this point, but the problem is not insoluble by any means.

There has actually been a pretty good conversation along these lines happening on the Seattle Robotics list lately. My argument is we already have the software and hardware capability to build the mythical "get me a beer" robot, but that is by putting together a bunch of existing technology buzzwords like SLAM, SAIT, and ZMP.

In order to build something that is much more general purpose, there is more than a cost issue stopping us. We don't know how to do AI, not at the level required for a robot to be as capable as say a dog or a three-year-old kid.

That's what I'm aiming for, but like most things, lack of money is a major hindrance. The whole "work 40 hours a week to pay the bills" thing really gets in the way of doing cool AI research...

- Jon

In order to build something that is much more general purpose, there is more than a cost issue stopping us. We don't know how to do AI, not at the level required for a robot to be as capable as say a dog or a three-year-old kid.

That's what I'm aiming for, but like most things, lack of money is a major hindrance. The whole "work 40 hours a week to pay the bills" thing really gets in the way of doing cool AI research...

- Jon

Re: History Repeats With the Personal Robot

The next few stages in personal robot evolution probably won't involve sophisticated A.I. -- complex neural networks, k-nearest neighbor classification algorithms, Gaussian mixture models, naive Bayesian classifiers, forward and backward propagation, and the like -- but they'll most likely have some sort of simple autonomous goal seeking, object recognition/avoidance, responses to stimuli, semi-random behaviors, etc. My Aibo has all these, but it's a stretch to call it true A.I.; more accurately, it's simulated A.I. But still, it's an order of magnitude more sophisticated and interesting than direct remote control of movements or manually invoking pre-programmed sequences. Inevitably, commercial personal robots will incorporate more sophisticated A.I. at some point, but it probably won't happen soon. Mind you, I'm not denigrating the current state of bipedal robotics, which is incredibly cool; I'm just looking forward to what's on the horizon with great anticipation, cheered by how rapidly personal computers evolved from a similar developmental stage.

I am not sure what you mean by personal robots. There are many types of personal robots over in Iraq and Afghanistan. As far as autonomous you can not get more autonomous then Global Hawk. If you want I can do more research and name you many more autonomous and personal robots over in Iraq and Afghanistan. I am also not counting all the research going on right now in robotics for different types of military use.

I am just trying to say that the revolution is happening right now and product testing is occuring in Iraq and Afghanistan.

I am just trying to say that the revolution is happening right now and product testing is occuring in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Gort wrote:I am not sure what you mean by personal robots. There are many types of personal robots over in Iraq and Afghanistan. As far as autonomous you can not get more autonomous then Global Hawk. If you want I can do more research and name you many more autonomous and personal robots over in Iraq and Afghanistan. I am also not counting all the research going on right now in robotics for different types of military use.

I am just trying to say that the revolution is happening right now and product testing is occuring in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Personal robots, like personal computers, are products that are available for personal use by individuals. They are designed primarily for the consumer market, as opposed to military, industrial, or institutional purposes. Certainly, developmental advances in military, industrial, or institutional robots may filter down to personal robots, but strictly speaking they are not "personal robots," because individuals cannot easily buy them. For example, the Kondo, Hitec, and Kyosho robots are personal robots. UniMate, Asimo, and Global Hawk are not; however, if their makers decided to market them to the general public then they would be personal robots, albeit very expensive ones. It's the market for which they are intended as well as their intended use that determines the classification.